This is such a tragedy. The story of the Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island deserves to be told. Apparently, the problem here was an inadvertent violation of Section 110 of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

Tag Archives: Kathleen O’Neal Gear

Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act…

- Friday, 27 March 2015 04:25

- 0 Comments

10,000 year old stone tools found in suburban Seattle…

- Thursday, 26 March 2015 14:06

- 0 Comments

Prehistoric petroglyph of buffalo hoof prints

- Thursday, 19 March 2015 21:26

- 0 Comments

At first glance this prehistoric petroglyph, rock carving, might look like eyes. When you get close, however, you can tell that it’s actually buffalo hoof prints. Above the prints are four carefully ground dots. You can see two in this photo. These are found about a five minute walk from our front door in a box canyon. What do they mean? Well, we wish we knew. We suspect they are from the Late Prehistoric Period, which means made within the last 1,000 years. Interestingly, this is the one side canyon on the ranch where prehistoric peoples could have trapped buffalo. Is that what the petroglyph documents? “We trapped buffalo in this canyon four times.” No one will ever know, but the petroglyph is a constant reminder that buffalo have been here a long time, and native peoples used them to feed their families.

At first glance this prehistoric petroglyph, rock carving, might look like eyes. When you get close, however, you can tell that it’s actually buffalo hoof prints. Above the prints are four carefully ground dots. You can see two in this photo. These are found about a five minute walk from our front door in a box canyon. What do they mean? Well, we wish we knew. We suspect they are from the Late Prehistoric Period, which means made within the last 1,000 years. Interestingly, this is the one side canyon on the ranch where prehistoric peoples could have trapped buffalo. Is that what the petroglyph documents? “We trapped buffalo in this canyon four times.” No one will ever know, but the petroglyph is a constant reminder that buffalo have been here a long time, and native peoples used them to feed their families.

Thanks to Mike and Annie Blakely for taking this great shot. Ours aren’t nearly as good!

Free Excerpt of THE DEAD MAN’S DOLL, our new short story…

- Wednesday, 18 March 2015 12:18

- 0 Comments

New e-short story coming! Read a free excerpt at http://www.dragonmount.com/eStore/ebook_samples/3699_The_Dead_Mans_Doll.php

For those planning to read THE DEAD MAN’S DOLL, you can now read a free excerpt at:

http://www.dragonmount.com/eStore/ebook_samples/3699_The_Dead_Mans_Doll.php

This e-short story is a prequel to our book coming out in May, PEOPLE OF THE SONGTRAIL about Viking exploration of North America around 1,000 years ago. Hope you enjoy it!

It’s a warm sunny day here. We only have a few patches of snow still lingering in the shadows of the cliff ledges. Pretty.

Visit Prehistoric Sites With Respect

- Sunday, 15 March 2015 10:25

- 0 Comments

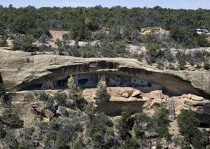

In the wonderful book, Visit With Respect, Tessie Naranjo from Santa Clara Pueblo, says: “Whenever I come to old Pueblo sites it is the beginning of emotions swelling up. About people, my people, my ancestors who used to live here. And connections with them. There is no past; there is no present. There isn’t a divide there. That’s why when we are here, we can greet the people who are here, who have not been here for hundreds and hundreds of years. It’s as if they are here right now and we can talk to them.”

One of the reasons it’s important to protect and preserve archaeological sites is to allow the public to experience that timeless moment that Tessie Naranjo speaks about so eloquently. In that eternal now it is possible, we believe, to transcend the barriers of time and touch the peoples who lived in America long, long ago.