The literary motif of Vikings and magical swords goes back over one thousand years, but it was J.R.R. Tolkien who made it part of the identity of modern peoples. This is a great article…

The literary motif of Vikings and magical swords goes back over one thousand years, but it was J.R.R. Tolkien who made it part of the identity of modern peoples. This is a great article…

MAGIC IN 10TH CENTURY VIKING CULTURE:

THE SEIDUR TRADITION

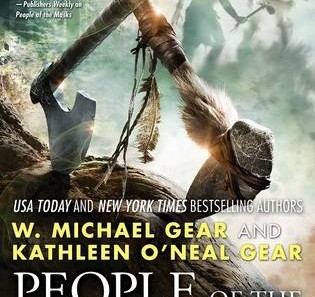

Since PEOPLE OF THE SONGTRAIL is coming out on Tuesday, we thought we’d talk about the Viking magical tradition called Seidur or Seidr. There are numerous modern shamanic movements that focus on Seidur–which are interesting in and of themselves– but this article will focus only on Viking Age archaeological and historical evidence for this highly magical shamanism. Which is cool stuff, by the way.

Seidur magic was Odin magic. Odin, who later became the chief god, was apparently merely a one-eyed war god when the 10th century began, but he was a powerful war god, and there are explicit descriptions of seidur magic in a number of medieval Icelandic texts. The most important of which are Edda’s Poems like Voluspa and Lokasenna, and great sagas, Gisli Sursson’s Saga, Eiriks saga rauda, and Hrolfs saga kraka, as well as Snorri’s Ynglingasaga.

Seidur magic seems to have been largely the sphere of women. However, Odin himself is said to have practiced Seidur magic, and we have historical references to male Seidur seers, though such men were generally maligned for engaging in feminine activities. Seidur magic had several goals: (1) Prophecy. For example, in Eiriks saga rauda (chapter 4), the seeress is trying to gain knowledge of the future. In Edda’s poem , Voluspa, she is concerned with the fate of the gods, the coming of Ragnarok. (2) Controlling the weather, or people, both of which are documented in Gisli Sursson’s Saga (chapter 18), and The Saga of the People of Laxardal (chs. 35-37).

Seidur seers also gained supernatural knowledge through utiseta, which means they sat outside at night on graves and sought out the secret wisdom known only to the dead. To accomplish these goals, the seeress engaged in rites that included fasting, hanging, exposure to the cold, spirit journeys, ecstatic trance states and shape-shifting. Seidur seers were apparently particularly adept at taking on the forms of bears, wolves, and foxes. As with other circumpolar shamanic traditions, we have hints that changing gender may have been part of some seidur intitation rites (see Meulengracht Sorensen 1980; 1983). As Neil Price noted in his excellent article, The Archaeology of Seidr (Lewis-Simpson 2000, p. 278), “It would seem to be the apparent contradiction of Odinn’s role as both a male god and the master of seidr—these rituals that were primarily the province of women—that gives him such extensive power over the minds and movements of others, and particularly over the events of the battlefield.” So, it was the combination of male and female powers–the crossing of gender boundaries– that were the source of seidur magic.

In conclusion, though it is rarely mentioned in books on Vikings, the highly magical seidur tradition was inextricably woven into the very fabric of Old Norse society. In fact, we would argue that you cannot fully understand Viking culture without an understanding of seidur seers and their magical influences.

The same is, of course, true of aboriginal Native American, Australian, and African cultures. Magic is at the core of spiritual traditions around the world. Including our own. Can you imagine any scholar of American culture passing over the miracles of Jesus, or the resurrection, or the virgin birth? The magic associated with the Ark of the Covenant as it was carried into battle by the ancient Israelites?

Magic is such an enormous part of who we are a spiritual beings that to leave it out of a cultural study is to miss the very heart of the people. And that is nowhere more true than with Viking archaeology.

READ MORE ABOUT IT!

PEOPLE OF THE SONGTRAIL

THE DEAD MAN’S DOLL

VIKINGS IN NORTH AMERICA

Lewis-Simpson, Shannon.

Vinland Revisited. The Norse World at the Turn of the First Millennium. Historic Sites Association of Newfoundland and Labrador, Inc., 2000: 277-294.